Gözde Kırcıoğlu on the silent impact of the Nansen Report on the 1923 Greco-Turkish population exchange convention.

Gözde is a PhD candidate at Leiden University.

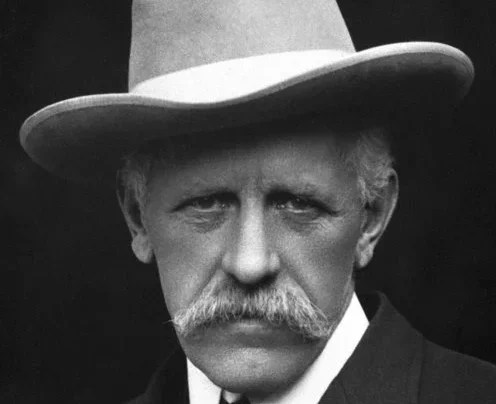

At the Lausanne Conference, no party wanted to be seen as the architect of the forced aspect of the Greek-Turkish Population Exchange. The Greek delegation blamed the Turkish side for pushing the idea, while also accusing Fridtjof Nansen, the League of Nations’ High Commissioner for Refugees, of introducing it. Meanwhile the Turkish delegation pointed fingers at the Greeks. This blame game has influenced both historiography and national rhetoric in Greece and Turkey ever since.

Nansen’s report, presented on 15 November 1922 at the opening session of the Conference, crafted a compelling narrative [1]. The report described Nansen’s six-week effort in Istanbul to broker a population exchange between Greece and Turkey, independent of any peace treaty. Nansen detailed his unsuccessful attempts to meet Mustafa Kemal Atatürk or any Ankara authority to discuss the matter.

The report suggested that Nansen’s efforts were thwarted by Turkey’s insistence on compulsory exchange and its rejection of voluntary solutions. A draft voluntary population exchange treaty was attached to the report, which had been sent to Ankara in November 1922. Ankara never responded.

What the report omitted, and what has only recently come to light in the literature, is that Nansen had already drafted a compulsory population exchange agreement.

What the report omitted, and what has only recently come to light in the literature, is that Nansen had already drafted a compulsory population exchange agreement, which the Greek government approved in late October 1922—one month before the Lausanne Conference began. Turkey never saw this document, and it was conspicuously absent from Nansen’s report.

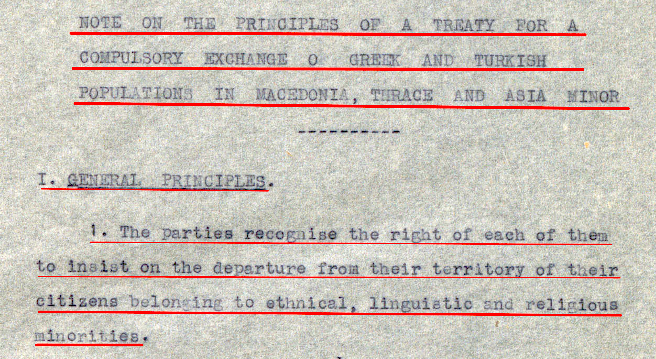

This draft agreement closely resembled the population exchange convention signed in Lausanne in January 1923, both being compulsory in nature. The first article granted both governments the right to enforce the departure of their citizens belonging to ethnic, linguistic, and religious minorities. The agreement targeted populations in Eastern Thrace, Central and Western Macedonia, and included provisions for individual registration and compensation for lost properties.

Notably, the draft did not protect the rights of approximately 300,000 Ottoman Greeks from Eastern Thrace and Western Anatolia, who had been forcibly expelled before August 1914 by the Committee of Union and Progress. The draft used the term “expelled citizens,” retrospectively affecting those who had fled since August 1914, the start of World War I. The Lausanne Convention, however, included people displaced since the Balkan Wars, that is since 18 October 1912.

The draft treaty referenced “Macedonia, Thrace, and Asia Minor” as areas of application but omitted explicit mention of Constantinople or Western Thrace. The Lausanne Treaty ultimately excluded these regions from the population exchange. At the time, the status of Istanbul and Western Thrace was still open to negotiation, but Athens did not consider the draft treaty to include the Orthodox Greek population of Istanbul, as later statements from the Greek Foreign Minister confirmed.

Upon returning to Istanbul from Athens on 24 October 1922, Nansen and his assistant Noel Baker encountered objections to the compulsory nature of the draft treaty from League of Nations officials Marcel de Roover and Erik Colban. These men were overseeing Nansen’s work—de Roover was the League’s appointee for the Greek-Bulgarian population exchange, and Colban headed the League’s Minorities Section. They drafted a new treaty based on the 1919 Greek-Bulgarian voluntary population exchange, also supervised by the League. This voluntary draft treaty ultimately appeared in Nansen’s report.

Colban argued that a treaty forcing both governments to expel large portions of their citizens would be a distasteful arrangement. He believed the goal should be an agreement that allowed Greeks who had fled Asia Minor and Thrace to settle in Greece, while Turks in Greece would return to Turkey, making room for Greek refugees. After discussions with Colban and de Roover, Noel Baker informed Geneva that the treaty was only a rough sketch and that no one should be alarmed by its “compulsory emigration” elements.

In summary, League of Nations officials Eric Drummond, the General Secretary, and Erik Colban intervened in late October 1922 to replace the compulsory population exchange treaty approved by the Greek government with a voluntary one. This voluntary draft was the version presented in Nansen’s report at the Lausanne Conference.

The omission of the compulsory draft treaty, approved by Athens before the Conference, significantly influenced the historical narrative. The creation and approval of a compulsory draft treaty by Fridtjof Nansen and the Greek government before the Lausanne Conference reveals a different story about how the decision for compulsion was made. Contrary to Nansen’s report, the League of Nations’ leadership, particularly Drummond and Colban, were the only ones to object to compulsion and successfully redirected negotiations towards a voluntary agreement.

Athens was the first to approve a compulsory population exchange treaty but rejected the expulsion of Orthodox Greeks from Istanbul. Ankara also wanted compulsion, including Istanbul in the treaty, and was transparent about its intentions. However, for the Ankara government, signing a population exchange agreement was a matter to be addressed after a peace treaty was finalized.

Note

[1] Fridtjof Nansen, “Report by Dr. Nansen: Reciprocal Exchange of Racial Minorities between Greece and Turkey, 15 Nov. 1922,” League of Nations Official Journal 4th year, no. 1 (January 1923): 126.

MAIN IMAGE: FRIDTJOF WEDEL-JARLSBERG NANSEN, NOBEL.ORG. OTHER IMAGES COURTESY GÖZDE KIRCIOGLU (NANSEN REPORT) AND LIBRARY OF CONGRESS (DRUMMOND).

Blogposts are published by TLP for the purpose of encouraging informed debate on the legacies of the events surrounding the Lausanne Conference. The views expressed by participants do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of TLP, its partners, convenors or members.